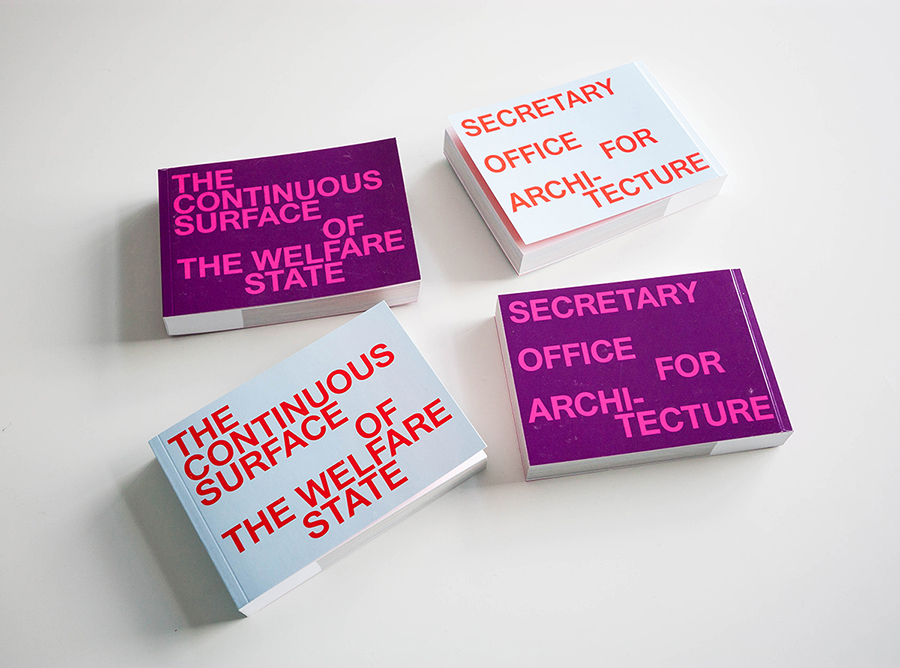

THE CONTINUOUS SURFACE OF THE WELFARE STATE

EXHIBITION/INSTALLATION

STOCKHOLM, MALMÖ, FALKENBERG, TOKYO,

2017-2018

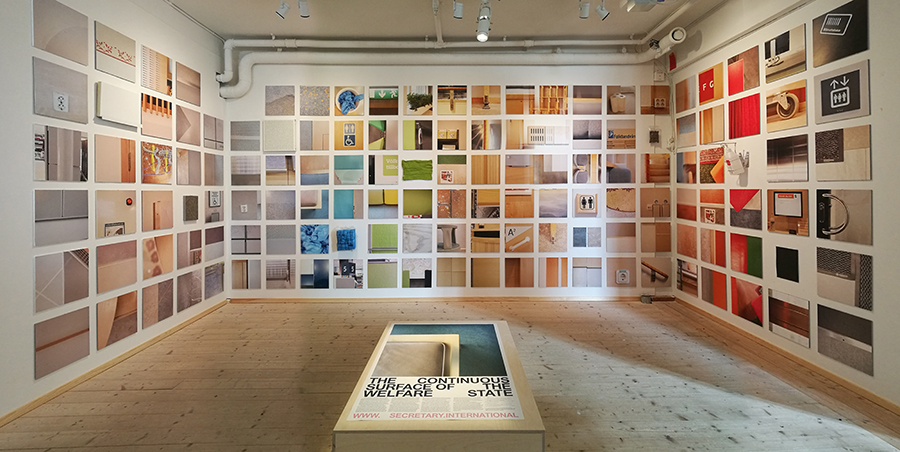

The Continuous Surface of the Welfare State was an installation that Secretary produced at the invitation of Zimmhall (Malin Zimm & Mattias Bäcklin) in January 2017 for the exhibition Välfärdsstatens Gränssnitt at Allkonstrummet, at Mossutställningar, in Stockholm, Sweden. Through a collection of images and material samples, displayed under a grid of suspended lamps, the exhibition performed a survey of the architectural surfaces where subjects meet the contemporary Swedish welfare state in their daily lives. The exhibition has since been re-exhibited as part of the Ung Svensk Form 2018 exhibition at ArkDes in Stockholm, at Form/Design Center in Malmö, at RIAN Designmuseet in Falkenberg and as a part of the Swedish Design Moves Tokyo 2018 exhibition during the Tokyo Design/Art Festival in 2018.

The spaces of the late Swedish Welfare State extend across hundreds of thousands of square meters, interior and exterior, taking in programs as diverse as healthcare, transportation, the chambers and offices of representative democracy, alcohol stores, education institutions, libraries, tax offices, galleries, and archives. Together, these spaces constitute a milieu—what Foucault might perhaps have called an “environmentality”—that embraces us as impersonally as possible, facilitating a life (any life, all life) in a manner that radically exceeds the tight, familial and communitarian circles of care envisaged by liberal bourgeois civil society.

This “state of things” is met by its citizens as a material interface: slick and sticky, permeable and durable; slow, monumental, and quotidian; and always deeply material. It is seldom, as we sit and wait for test results or ease a sleepy body into a swimming pool before work, that we perceive these spaces as components of a broader infrastruc¬ture, and yet this is what they are—vital parts of what Judith Butler refers to as a “supportive environment” [1], a broader “surface” that bears, affects, shapes, and facilitates life. Whilst the voices of feminists have raised sharp and necessary critiques in relation to the architectures of the Welfare State over the past century [2], feminism’s resistance to view of the subject as sovereign and independent (as capable of acting without being acted upon) also suggests the value of a “habitable ground,” an environment that supports us in our social and material interdependencies. The choice to read architecture as a “continuous surface” is an attempt to bring this environment into view as an object of investment, maintenance, political struggle, and architectural design.

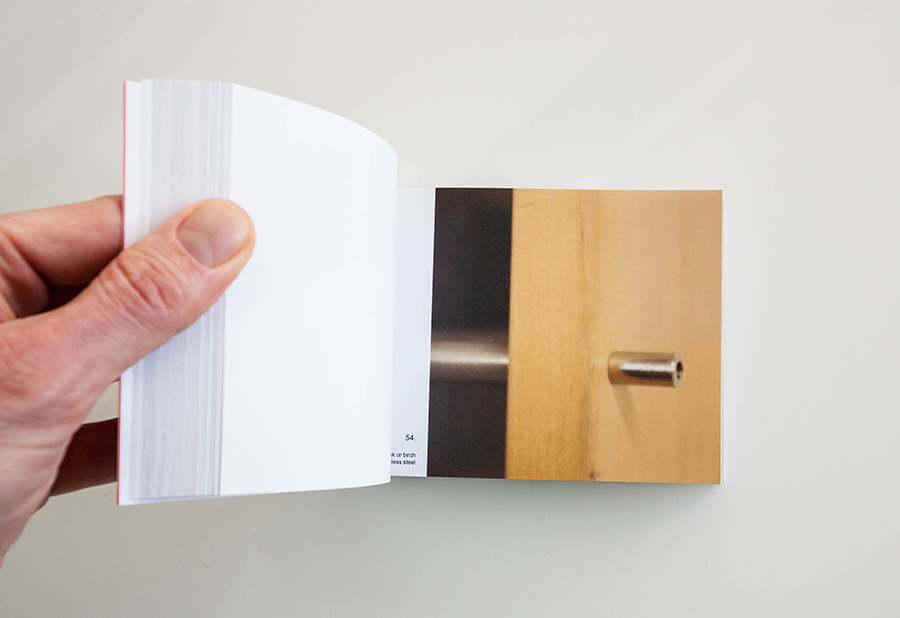

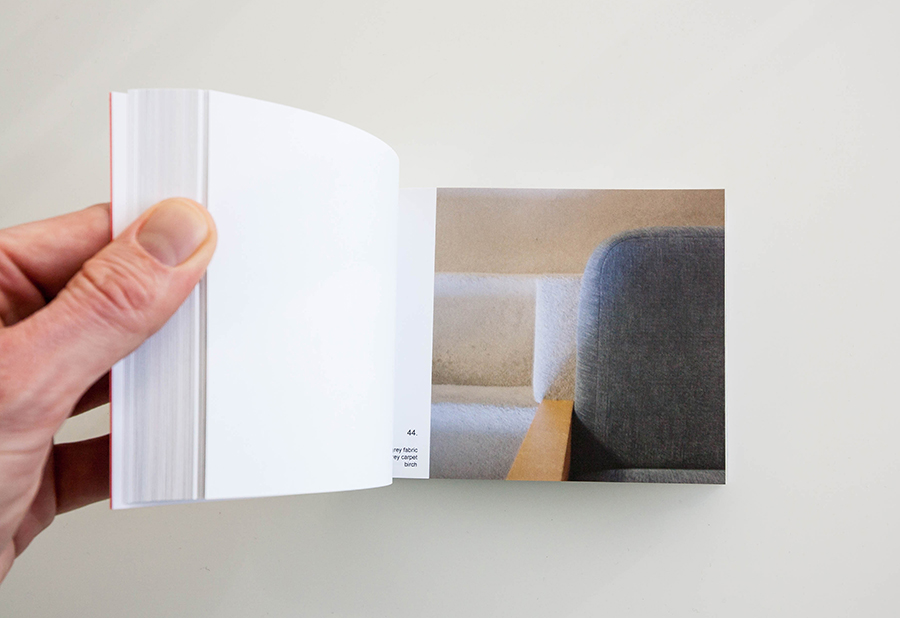

Marbled linoleum, white perforated suspended ceiling panels, birch wood, the ubiquitous Swedish limestone Jämtlänsk kalksten. The consistency of materials seen in the Swedish public interior reveals a history that moves slowly. In a material culture characterized by accelerating trend cycles, the persistence of materials that were “popular in the 1990s” some 20 years later is evidence that the public interior, beyond nostalgia and obsolescence, is also a site for enduring and robust treatments, resistant to the “throw-away” culture that dominates the treatment of our private interiors. Within these established palettes and aesthetics, changes in procurement procedures, advances in material science, shifting maintenance procedures, and radical rifts in mentalities of governance ripple across the surface, leaving imprints in the form of repeated furniture, textiles, structural systems, and spatial qualities (scale, light, complexity) behind them.

Bored, lonely, nervous, jubilant, we meet the state in waiting rooms, over reception desks, in the approach to counters, in hallways. These spaces in turn embrace us as impersonally as possible. Michel Foucault, in a discussion of the state phobia of neoliberalism, notoriously observes that “the state has no heart… not just in the sense that it has no feelings, good or bad, but that it has no heart in the sense that it has no interior. The state is nothing else but the mobile effect of a regime of multiple governmentalities.” [3] This “heartlessness” aligns with Claude Lefort’s diagnosis of democracy as being founded on “the image of an empty place,” a formulation deployed by art historian Rosalyn Deutsche borrows in her defense of the centrality of public space to democracy [4]. In democracies, energy must be expended in making sure that a singular sovereign power is absent, an absence which requires continual reinforcement, renewal, renovation, and investment. [5] Thus, as Nina Power has recently argued, if feminism must assert ownership over the concept of “nothing”—thereby reclaiming it from male artists and masculinist philosophers [6]—a similar move might be called for in considering democratic architecture’s “void,” its empty place.

In a moment characterized by the compulsion to constantly communicate, it is perhaps finally in the waiting rooms of the tax office, gynecologist, fitness center or train station that we can ignore contemporary demands to dress for the occasion, to publicize our presence, and to be ourselves. In these spaces, we can assert an emancipatory claim to a democratic architecture of the void. Drawing away from us slightly in their impersonal ubiquity, the architectures of the continuous surface thereby give us space, compelling us to sit or walk or swim or sleep or wait together, in all of our social and material interdependence.

NOTES

[1] Judith Butler, “Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance,” in Butler, J., Gambetti, Z., & Sabsay, L., eds., Vulnerability in Resistance (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 15.

[2] See for instance, Katherine Schonfield, “Why Does Your Flat Leak?” in Walls Have Feelings: Architecture, Film, and the City (London: Routledge, 2000).

[3] Michel Foucault, “31 January 1979,” in The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978-1979 (New York: Picador, 2004), 77.

[4] Deutsche quotes Claude Lefort. Rosalyn Deutsche, Evictions: Art and Spatial Politics (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1996), 273.

[5] Helen Runting, “Desiring Democracy,” in Aiming for a Democratic Architecture (Stockholm: The Swedish Association of Architects, 2018).